Philip Crawford, Self Defense Made Easy (No.1) – Video & Prints

Philip Crawford, Self Defense Made Easy (No.1) – Video & Prints

Self Defense Made Easy (No. 1) explores black American martial arts instruction as a mechanism for radical social, political, and epistemological liberation. Fusing the discipline of the body and mind, various adaptations and appropriations of non-Western self-defense techniques have filtered through black communities in America for centuries. Often linked to religious and political movements, these kinesthetic systems continue to generate new ways of knowing the self. While Philip Crawford’s work draws most iconically from the popular sounds and images of 1980s kung fu culture, his research also considers the earlier roots of black American martial artistry and unarmed self-defense linked to slave uprisings, religious communities, military service, solidarity with global anti-imperialist movements, and the rise of Black Power.

Central to Self Defense Made Easy (No. 1) is an appropriated and reanimated sequence from a martial arts instructional video (“Self Defense Made Easy,” 1989, Century Film Studios, New York). In that sequence, Shidoshi Ron Van Clief instructs learners in the proper technique for the Snake Fist, an open-hand form characterized by swift and powerful strikes to an opponent’s vital areas, including the face, throat, and neck. Throughout his demonstration, Van Clief reminds practitioners to relax and to breathe. He directs us to carefully tuck our thumbs under our palms so that we can effectively strike the eyes of an opponent without incurring self-injury.

This strike is to the eyes.

Maintain a relaxed breathing pattern.

Back straight.

Head erect.

Fingers straight.

And always tuck those thumbs,

in order not to incur injury to yourself.

RELAX

Philip Crawford’s efforts to decipher this cultural artifact are joined by his focus on the relation between notions of selfhood and practices of self-defense in communities excluded from Enlightenment definitions of self. Of particular interest to his study are the ways in which instruction in martial arts as kinesthetic knowledge is not only an education in violence or protection, but more fundamentally an education in individual and communal self-making. This instruction provides the basic means for defense that must be creatively applied to claim epistemological space, build social and political communities, and form new models of self-care. For Crawford, lingering in moments of martial arts instruction offers a means of referencing both a natal moment of black self-making and the multi-faceted and improvisational nature of black practices of self-defensive care.

This study finds echoes in the work of Fred Moten in suggesting that the complex response of black and other marginalized communities to the regulatory effects of exclusionary definitions of self requires constant practice in improvisation. In In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (2003), Moten notes that if black radical performance is grounded in the aesthetic practice of improvisation, it is so because improvisation is the condition of possibility for black social life in an anti-black world. Put differently, the performance of black selfhood demands constant improvisation in and around exclusionary definitions of who can claim the status of the human or the subject.

foresight: /ˈfɔːr.saɪt/ the ability to judge correctly what is going to happen in the future and plan your actions based on this knowledge

Improvisation is most commonly understood as speaking or acting without foresight, as implied by the term’s Latin etymology. Yet Moten reminds his readers: “That which is without foresight is nothing other than foresight” because “improvisation, in whatever possible excess of representation that inheres in whatever probable deviance of form, always also operates as a kind of foreshadowing, if not prophetic, description” (Moten, 63). In this exhibition, the appropriated instructional video documents a transmission of the knowledge required for such foresight-less foresight. Its lessons are broadcast, to paraphrase Moten, across that unbridgeable chasm between disarmament and preparation, feeling and reflection.

BREATHE DEEPLY

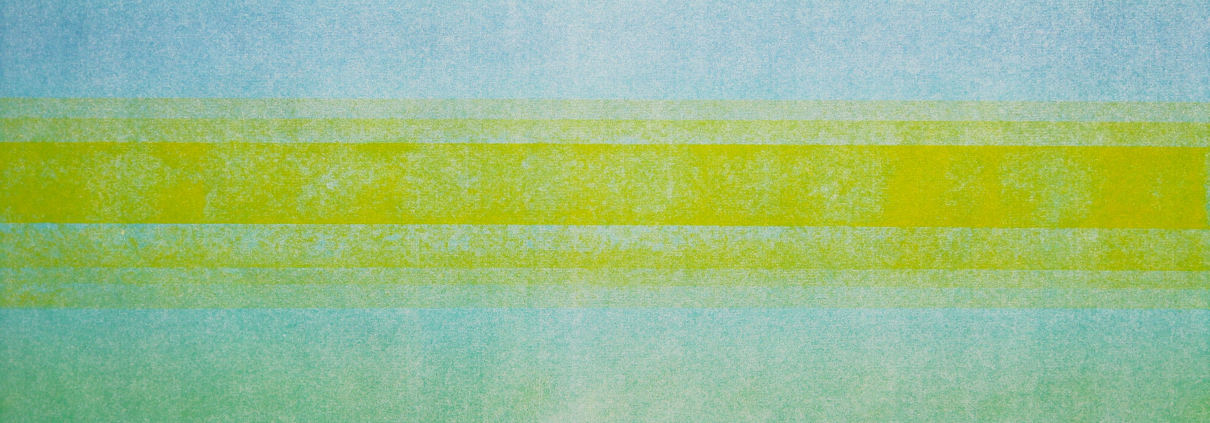

The looped animation and softly pixelated prints in Self Defense Made Easy (No. 1) focus on the “strike to the eyes” not as a moment of aggression, but as a call to self-making and preparation for the improvisational demands of self-defensive care. “Practice, practice, practice,” Van Clief calmly intones as he demonstrates the various moves of his technique. Head up. Straighten fingers. Tuck thumbs. By presenting this simple movement at a lower frame rate, Crawford slows down the image so that it might be more closely read. Throughout the exhibition, the artist offers particular focus on the noise present in each image: the carefully pixelated grain, the elusive flicker of the screen, the motion blur of the body, the yellowed cascade of the scan lines. These chaotic and unpredictable elements that he highlights mark an excess of visual information that may appear to viewers as a deviance of form. However, it is the very failure to adhere to form (to be aberrant, unruly, hypervisible) that carries with it the radical trace of improvisation. In refocusing our attention on these visual artifacts, Crawford proposes that if we approach these images at a different pace we might achieve a different sense of their legibility.

“Improvisation must be understood, then, as a matter of sight and as a matter of time, the time of a look ahead whether that looking is the shape of a progressivist line or rounded, turned. The time, shape, and space of improvisation is constructed by and figured as a set of determinations in and as light, by and through the illuminative event.” (Moten 64, emphasis in text)

In this exhibition that altered pace is set by Yellow Bar (Restoration of a Visual Artifact) (2022, Animation, 2:06 single channel with sound, looped). This time-based work renders visible what is normally invisible, as Crawford attempts to restore the visual anomalies he experienced when viewing the original VHS document. The restored yellow bands, which appeared due to a difference in frame rate between analog and digital mediums, are established through this animation as a primary protagonist in the exhibition. Their perceptibility reveals for the viewer that “slightly different sense of time” that Ralph Ellison describes in the famous prologue to his novel Invisible Man:

“Invisibility, let me explain, gives one a slightly different sense of time, you’re never quite on the beat. Sometimes you’re ahead, sometimes behind. Instead of a swift and imperceptible flowing of time, you are aware of its nodes, those points where time stands still or from which it leaps ahead.” (Ellison, 8)

In the looped video, it is the shifting of the yellow scan lines that define a seemingly erratic beat. The irregular stillness of the hand, its attenuated motion, raises questions about its intent. Does the halting hand gesture, which enacts the instructions for a defensive strike, double as a gesture of hailing? Is the figure, who we cannot see, calling us closer or warning us away? Is it a demand for recognition? Is it a wave to counter the invisibility that Ellison ascribes to “a peculiar disposition of the eyes of those with whom I come in contact” (Ellison, 1)? In any case, the gesture recalls the simultaneous invisibility of blackness (in the unrecognized subject of politics, perhaps, as suggested by Saidiya Hartman) and the hyper-visibility of blackness (which elicits the need of constant surveillance from the eyes of a world shaped by the peculiar disposition of anti-blackness, as suggested by Simone Browne). If black self-defensive care – which is to say black social life – is routinely misread as an act of aggression, the inscrutable hand gesture in Yellow Bar takes hold of this reading practice and reflects it back to the viewer.

REPEAT

Reading with but not through the noise, we might see that the act of instruction is offered not in the interest of regulating the black body, but to provide any means necessary for improvisational, applied self-care. Practices of self-making demand repetition: live variation whenever and however they are applied. The liminal space between true repetition and practiced improvisation is mirrored in Crawford’s translation of still images from the instructional video to paper. Each of the resultant printed “copies” challenges the medium’s assumption of reproducibility, and, in that challenge, troubles the stability of the image. In particular, the variety and irreproducibility of the color field screens–each of which holds its own space as a separate moment in the act of instruction and in the process of making–draw focus away from the body (which becomes an absent presence) and to the flicker of light from the screen before it strikes your eyes.

The visual noise that Crawford tends to is the clearest aesthetic representation of the improvisational practices required for the complex performance of black selfhood. In Self Defense Made Easy (No. 1) the artist asks us to slow down, to relax and breathe deeply, to join his study of these images, and then to do it all again.

Works Cited

Browne, Simone. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Duke University Press, 2015.

Ellison, Ralph. Invisible Man. 1952. The Modern Library, 1994.

Hartman, Saidiya V. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. Oxford University Press, 1997. p 61.

Moten, Fred. In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition. University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

Artist Statement

The study of “fast images” is central to my artistic practice. I investigate ways to slow down their reading to unsettle hegemonic historical narratives, challenge systems of oppression and reclaim technologies of power. In my work, fast images take the form of visual representations, statements, objects and sounds appropriated from popular culture. Common and commodified, these things are fast not only because of the speed at which they are produced and consumed, but because the narratives they transmit easily conform to the ways we expect the world to be.

Comic books, religious tracts, household appliances, film memorabilia and other popular artifacts become narrative frames and material resources for an interdisciplinary studio practice that includes works on paper, sculpture, installation, video and performance. Through the intertextual layering of these appropriated traces, I hope to activate a dissonant, speculative nostalgia that allows us to reconsider our pasts, presents and futures.

More information on Philip Crawford here.

Program:

Friday, 28 April 2023, 18.00 h

Vernissage. The artist will be present.

Saturday, 13 May 2023, 16.00 h

Artist Talk with Philip Crawford.

Saturday, 10 June 2023, 17.00 h

Finissage.

Philip Crawford , Self Defense Made Easy (No.1)

29 April – 10 June 2023

Vernissage: Friday, 28 April 2023, 18.00 h

Where: nüüd.berlin gallery, Kronenstr. 18, 10117 Berlin-Mitte, U Stadtmitte

Open: Thursday – Saturday, 13.00 – 19.00 h